Bridging The Gap: Conditioning for Combat Sports

By Geoffrey Chiu

The training industry has come a long way since the time when tire flips and sledgehammer tire slams were the gold-standard for building endurance in MMA. As the sport becomes more popular and the quality of education for trainers improve, the way we approach conditioning should also improve. In the modern industry, it’s now about air-dyne assault bikes, mobility flows, perfectly crafted work-to-rest ratios and the use of heart rate tracking technology.

While there is nothing flawed with the current methods, I want to take a step back, revisit the components that make up conditioning performance in the world of combat sports and consider the application of these methods. My goal is to equip coaches, especially new coaches entering in the world of combat sports, with the knowledge needed to tackle the complexities that these combat sports possess.

While there is nothing flawed with the current methods, I want to take a step back, revisit the components that make up conditioning performance in the world of combat sports and consider the application of these methods. My goal is to equip coaches, especially new coaches entering in the world of combat sports, with the knowledge needed to tackle the complexities that these combat sports possess.

Many expressions are used to understand “conditioning performance” in combat sports, ranging

from casual, to formal and scientific:

- “How many rounds can you go?”

- “He gasses whenever he has grappling exchanges”

- “The goal of fight camp is to currently develop the energy systems used in MMA

- “We need to improve his anaerobic capacity”

All of which are acceptable when used within appropriate contexts, but ideally we would use a specific, common language, so everyone is on the same page.

When stripped to its core, conditioning performance in combat sports is the product of repeatability of effort and in-competition pacing.

Repeatability of effort (ROE) refers to an athlete’s physiological capacity to sustain a set of skills that are specific to the velocity and external load of the movements. To me, this definition is more pragmatic and guides practice better than simply using energy systems to define conditioning.

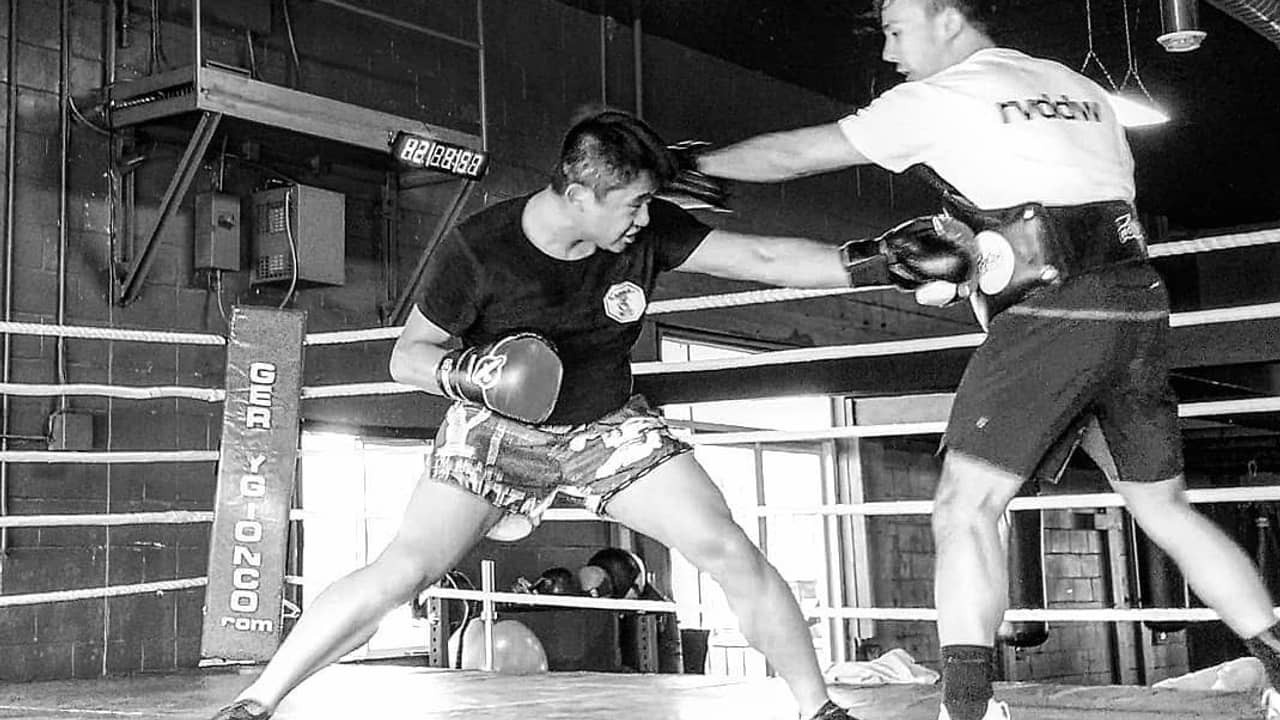

Two opposing set of skills, even though executed for the same work and rest duration, will have contrasting physiological demands. For example, the capacity to sustain high-velocity strikes with no external load (think of the classic striker) differs from the ability to sustain lower-velocity movements with high external load (think of the classic grappler), despite the fact that both classes of athletes possess elite level conditioning within their domains.

ROE is influenced by the capacities of the components that make up our energy systems such as cardiac output, lactate shuttling ability, lactate tolerance as well as the neuromuscular activation and oxidative properties of our muscle fiber types.

In-competition pacing refers to a fighter’s psychological management of energy expenditure during a match or fight. This management of energy is influenced by the strategy/game plan, the fighter’s conscious and unconscious reactions to the incoming stimulus as well as the energy demands of the cognitive load the athlete is facing.

Cognitive load is the amount of mental information the athlete is processing. This load increases if the incoming information is complex, novel and/or unpredictable. In combat sports, this means facing an opponent that:

- Possesses physical traits or skill sets the fighter has not been exposed to before.

- Possess a set of skill that the fighter does not have a clear answer to.

- Utilizes “unusual” or “unique” movement to stay unpredictable.

- Employs a strategy the fighter is not prepared for.

The high skill-ceiling of grappling and striking sports requires combat sport athletes to be information-processing beasts. Athletes must keep track of the combinations and movements the opponent has attempted thus far in the match, react to any strikes or submission attempts at any given moment, as well as plan 2-3 steps ahead in order to put themselves in a favorable position to execute their techniques – all while facing the painful, physical consequences of making a mistake anywhere along the way.

When experienced fighters and coaches say that fighting is as mental as it is physical, this is what they mean. The energy demands from the psychological efforts of dealing with cognitive load in combat sports should not be understated.

Conditioning Paradigms and Heuristics

Here are some conditioning paradigms and heuristics we can extrapolate from the interaction of the variables discussed above.

Firstly, know the principles that these sports were created on:

- Martial arts seen in combat sports were created to equip the weaker, more fragile solider with the tools to succeed in battle and war

- Combat sports is more so a competition of skill than raw physical ability

A fighter’s conditioning performance cannot be evaluated by repeatability of effort and physiological measures alone.

Poor performance can result from poor pacing – an athlete can gas out due to poor management of energy expenditure, despite possessing elite-level conditioning on paper. You cannot optimize performance by solely improving the engine and gas tank without making improvements to the driver.

Conditioning training should consider reducing the cognitive load the athlete will experience in-competition

S&C coaches must refine conditioning prescriptions to align with the combat athlete’s individual skillset and the development of their sport-specific skills through their camp and career

Putting It into Practice

What does this mean practically and how do we use these paradigms to inform the way we better develop conditioning in our combat sport athletes?

Conditioning Specificity & Integration

Along with the prescription of work-to-rest periods that emphasize certain energy systems, each conditioning modality lands on a continuum of specificity. In other words, how similar are the

Along with the prescription of work-to-rest periods that emphasize certain energy systems, each conditioning modality lands on a continuum of specificity. In other words, how similar are the

movements, and cognitive demands of the skill/training being practice compare to the skill being displayed and performed in competition?

In the strength & conditioning industry discourse, 30 seconds on, 120s off (1:4 work to rest ratio) is considered to be training and emphasizing the characteristic of “anaerobic capacity”. Yet, this conditioning protocol will yield different training adaptations when performed on the air dyne bike, versus performed against a live opponent through wrestling drills.

This concept is nothing new, coaches know this as dynamic correspondence, or the transfer of training to performances, but several nuances arise when considering the conditioning development in combat sports.

Sports practice should be the top priority of any athlete, but even more so in combat sports due to the plethora of techniques and skills to learn and develop. Conditioning must be integrated into a martial artist’s training schedule to better facilitate skill development and acquisition.

One of the most practical ways we can achieve this is implementing work-to-rest-ratios directly to skills training and drills. Ideally, martial arts coaches would teach their classes or set up the training camps in accordance to best practices that can develop both skills and the desired aerobic, anaerobic or alactic adaptations concurrently. I imagine this can be an obstacle for the majority of coaches out there that have no say in how sport practice is run, or have no contact with the sport coaches directly. That is another problem in itself that we won’t be touching on in this article.

The alternative is to be more meticulous about the conditioning training we as S&C coaches prescribe to our athletes. Lately, I’ve seen great value applying self-directed solo heavy bag, and shadowboxing intervals for my striking athletes as part of their conditioning off the mats more frequently, over more traditional modalities like road work and air dyne bike intervals. This is especially true for novice and intermediate martial artists with still so much room for technical growth. Any time they train closer to the sport’s constraints, it is an opportunity for them to improve.

This is a real-world example of a conditioning session taken from one of my fighter’s training program.

SAMPLE CONDITIONING SESSION

45 Min Duration (not including warm up, mobility and stretching)

Heavy Bag Intervals [5 x 3 Minute Rounds with 2 Minute Rests] – 25 min total duration

- Each round consists of 15 seconds maximum effort combinations, with 45 seconds of

easy effort strikes - Cues used: “Pick 2-3 of your favorite combinations and stick with those during hard

efforts, move your arms with light shots and work on moving your feet and head during

easy efforts, visualization is key”

Shadow Muay Thai Cooldown [1 x 20 Minute Round, nose-breathing only]

- Visualize your shorter opponent, visualize the need to maintain distance

- Utilize jab and teep frequently

- Keep heart rate in zone 2-3 for the whole duration of the round

- Do not let technique deteriorate as the round progresses

The goal with the heavy bag intervals is to develop power-endurance specific to striking – his ability to sustain bursts of high power output with periods of active rest dispersed throughout.

The shadow muay thai round is used to develop his aerobic system within certain constraints that are related to the development of his striking-skills and upcoming fight strategy. The elements of “nose-breathing only” and a long 20-minute round forces the athlete to improve on their internal pacing system (keeping heart rate and output below lactate threshold) while simultaneously maintaining mental acuity in context to the skill-related tasks (visualize shorter opponent, practice the jab and the teep).

This way, not only are we able to emphasize energy system development by utilizing the appropriate work-to-rest ratios, but we’re able to target repeatability of effort that is directly specific to their sport. Road work, skip rope and versa climbers still have a place in strength and conditioning. I’m humbly re-evaluating the benefit-to-cost ratio of such modalities considering the priority that skills training should hold more heavily in modern day combat sports.

Rethinking Lactate/Anaerobic Based Training

The glycolytic system has the smallest window of trainability, and creates an inproportionate amount of fatigue relative to the adaptations it creates.

This is not to say anaerobic performance shouldn’t be trained, anaerobic capacity is an important performance measure in many combat sports. However, by performing a high amount of lactate-based training in the weight room, it cuts into an athlete’s development of power, power-endurance and their ability to recover for their sports practice, sparring, drilling and rolling sessions.

The large majority of high-lactate producing and fatiguing anaerobic training should be performed in sports practice. Build lactate tolerance and anaerobic capacity within the constraints of the sport. Leave the most fatiguing type of training in the practice room, where athlete’s see the highest level of training specificity.

My high/low philosophy of athletic development has strengthened with over the years with experience. I believe it’s our job as coaches to raise the ceiling of an athlete, meaning develop maximum strength, power, power-endurance, and plyometric ability. Alongside raising the floor/base - keep the joints healthy, maintain high movement quality and increasing their lactate threshold and lactate shuttling ability by improving their aerobic energy system.

This philosophy compliments the paradigm that sports practice is king and should be highly prioritized and that strength & conditioning for combat sports training should add to the capacities of an athlete, not interrupt or take away from them.

Bridge the Gap

Let’s be clear. Despite what modern strength and conditioning coaches preach on social media to justify their conditioning protocols, no combat sports athlete ever acquired championship rounds conditioning performing intervals on the air dyne. Physicality alone is not the driving factor behind success in combat sports. The best combat sports athletes have put thousands of hours in skills practice to develop an elite ability to pace themselves in competition, process information and make decisions under pressure.

Bridging the gap between conditioning preparation and performance will require efforts from both sides:

- Sport coaches need to learn the fundamentals of energy system development in order to better support skill acquisition and development in their martial artists. The days of running athletes into the ground in order to build endurance and mental toughness should be over.

- Strength and conditioning coaches should avoid prescribing poorly-selected conditioning protocols that add no value to the development of the combat sports athlete just because of what is traditionally done in other sports, or the fact that many of coaches before them have done so. Most importantly, we should also learn more about the sport at hand by participating in or watching skills practice more frequently.

Ultimately, the future of conditioning for combat sports performance lies in the communication and collaboration between sport coaches and conditioning coaches, and both groups’ willingness to educate themselves in each other’s field of knowledge.